Anatomy of a Choral Arrangement - A Thousand Years

The “Anatomy of a Composition” series of articles is for anyone interested in the composition process, or for Music Theory teachers and students. These articles will supply enough information to understand the basic elements of the song, while allowing for independent study of the particulars of each element. If you need more information, please Contact Us. We’re always glad to help people learn about composing and arranging.

This article contains some technical music theory terms. If you need help remembering a term or two, there is a glossary of terms at the end. There may be more definitions than you need.

The song A Thousand Years by David Hodges and Christina Perri is a pop hit from 2011 that was written for the Twilight Saga, a series of romance fantasy films based on the book series Twilight by Stephenie Meyer. Click HERE to go to the Salt Cellar web page with info about A Thousand Years. There, you’ll find links to the YouTube video, print sample and purchase option.

Reason I Arranged This Song

I chose to do a choral arrangement of it for a number of reasons.

- It’s beautiful. And, it has a quiet sense of vigor. Unlike many pop tunes which concentrate on a bland series of notes over an equally insipid chord structure, this song has some real body and style to it, and incorporates some simple but effective classical techniques.

- It has a timeless lyrical theme in it – the promise of love and the fear of losing it. Also, many of the lyrics are presented in a stream of consciousness style, rather than full sentences. (Stream of consciousness lyrics present word pictures, often of common or well-known situations. This method often has more punch to it than normal sentence style lyrics.)

- It offers a number of arrangement options – parts, voicing, harmonies, and a few other things that suggest great modifications for a choral group.

Key Choice

The original song, as sung by Christina Perri, is in the key of Bb, which suits her range and expresses the warmth that this song conveys. This arrangement is in the key of F because it allows for the same warmth without requiring the choral singers to go out of their range.

If it was in the original key of Bb, the sopranos would have to sing a high Bb. Many could do it, but it would not at all be warm. Also, the bass part is easily singable, although it sits just a little higher than other bass parts in other songs.

Time Signature Choice

Occasionally, I will choose a different time signature for a song if I think it will enhance the presentation or add some needed color. You can hear two songs in which I changed time signatures. Listen to How Sweet the Sound and Now I See on the Choral Main Page for examples of altered time signatures.

Chord Structure and Voicing Choices To start, the structure of the song is virtually identical to the original. It was well thought out and there seemed to be no need to change it.

- Intro – The intro is simply a transcription of the original from Bb to F. This offers listeners a sense of familiarity, presuming they have heard the song before.

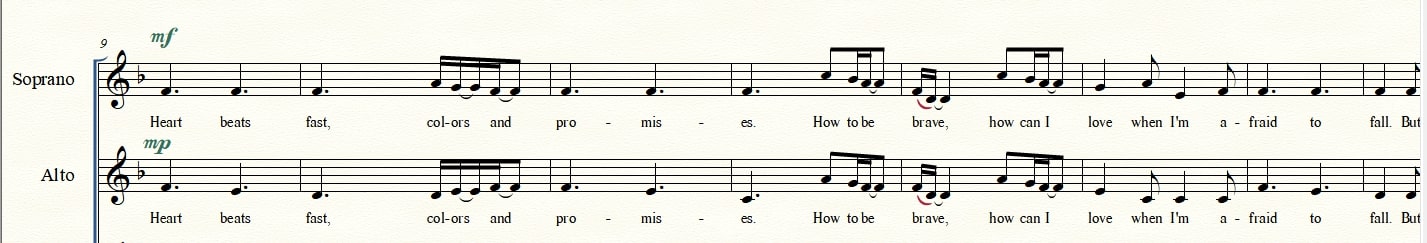

- Verse 1 – The first verse is sung by the female parts and immediately differs from the original in that the alto part creates some dissonance in a descending part. Then, the altos offer an ascending contrast motion to the sopranos descending part. On the word “Brave” the parts are in unison only for that word, giving it an extra sense of strength. The temporary dissonance and contrasting motion is repeated a few more times in this verse.

- Chorus – The chorus comes on with a bang, portraying the pain felt through the phrase, “I have died…”. The tenors and basses pound out their parts, often leaving the bulk of the lyrics to the female parts while the men drone their parts as a solid foundation.

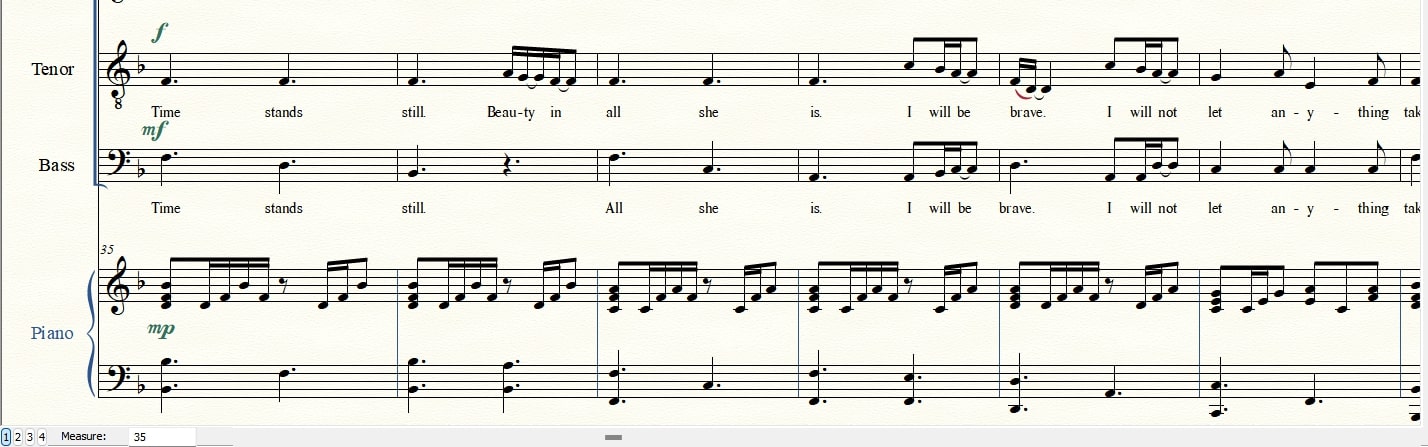

- Verse 2 – The male voices have the privilege of singing the second verse. The melody in it is the same as the first, but the harmony had to be different because of the range of the parts. Voices, and instruments, in lower registers can’t have harmonies that are too close. If they do, it sounds quite muddy and nearly unintelligible. It has to do with the Overtone Series. The overtones produced by low notes, whether vocal or instruments, clash at the frequencies that human ears hear best, and produce a very “confused” sound, that audibly disagreeable muddy sound. (Please see deeper explanation of the overtone series at the end of this article.)

- For the first part of the second chorus, the roles are virtually reversed. The female parts sing a “drone” part while the men sing the melody and harmony for the chorus. Then the roles are switched for a while and the women sing melody and harmony while the men provide a foundation in their parts. For the final phrases, the parts settle into more traditional roles, sopranos with the melody and the rest providing harmony and foundation.

- The piano break is a fair rendition of the break on the recording. No real surprises there.

- Mirroring the recording, the women sneak back in for a repeat of the chorus, with the men repeating their foundational part halfway through. This repetition of the chorus has a wispy texture to it, as if the singer is thinking, wishing, and hoping for the best.

- The final piano coda diverges somewhat from the recording, while still capturing the ethereal essence of it.

Instrument Changes

Because the music must be able to be used for choral contests and other competitions, the only accompaniment allowed is a piano. For that reason, I had to reduce the rhythms and harmony parts from the recording into a single piano part. This one wasn’t too difficult because the original recording arrangement is piano led. Some of the other rhythms were subtly provided by the accompanying vocals parts.

Secret(s) in it

There aren’t any real secrets in this arrangement. They are more likely to appear in an original composition where I know the origins of the musical phrases, chord progressions and the like. This arrangement does use some symbolic devices.

- The divergence and subsequent convergence of some of the lines symbolize the feared loss and hoped-for rescue of the relationship that the song portrays.

- There are a number of places in which the harmony could have been rendered closely but, instead, was done more “openly”. This not only sounds warmer, but depicts the “hollow” feeling one has when waiting for a relationship to grow.

I hope that this unfolding of the arranging process will help you understand this arrangement better and be more likely to use it, and other compositions and arrangements at Salt Cellar Creations, for your choral group.

Salt Cellar Creations has a growing library of original works and arrangements that not only sound great when your ensemble plays or sings them, but are equally suited to music theory analysis. Find out more about the available music Salt Cellar Creations HERE.

SCC can also compose an original piece for you or do a custom arrangement for you. There are two ways that this can be done; one is much more affordable than the other. And SCC is always looking for ideas of pieces to arrange or suggestions for original pieces.

We have sold music not only in the US but in Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and New Zealand, Austria, and Germany. Please visit the WEBSITE or CONTACT US to let us know what we can do for you!

OVERTONE SERIES EXPLANATION

The overtone series has been explained in a variety of ways, all of them correct but seemingly incomplete. For a much more complete discussion of the overtone series, see the article about it HERE.

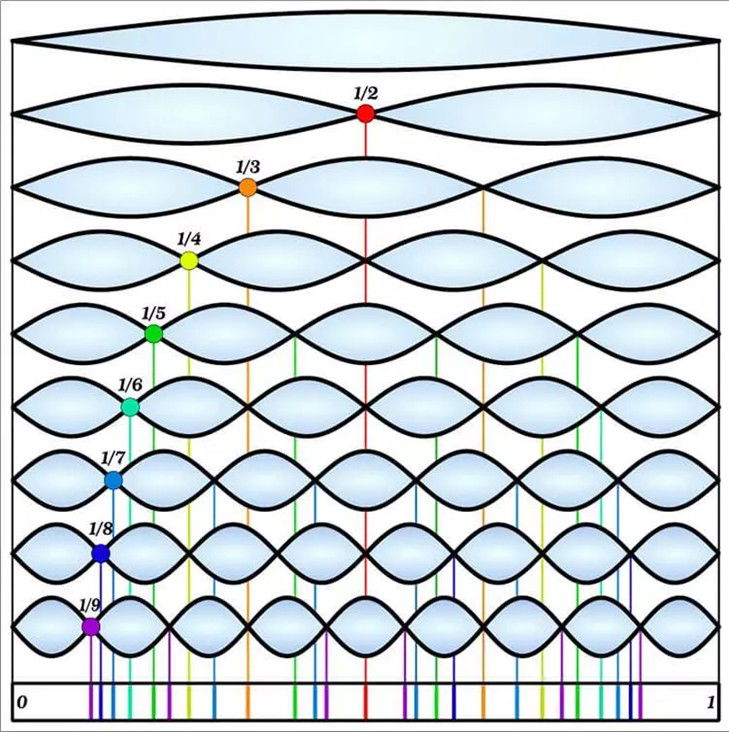

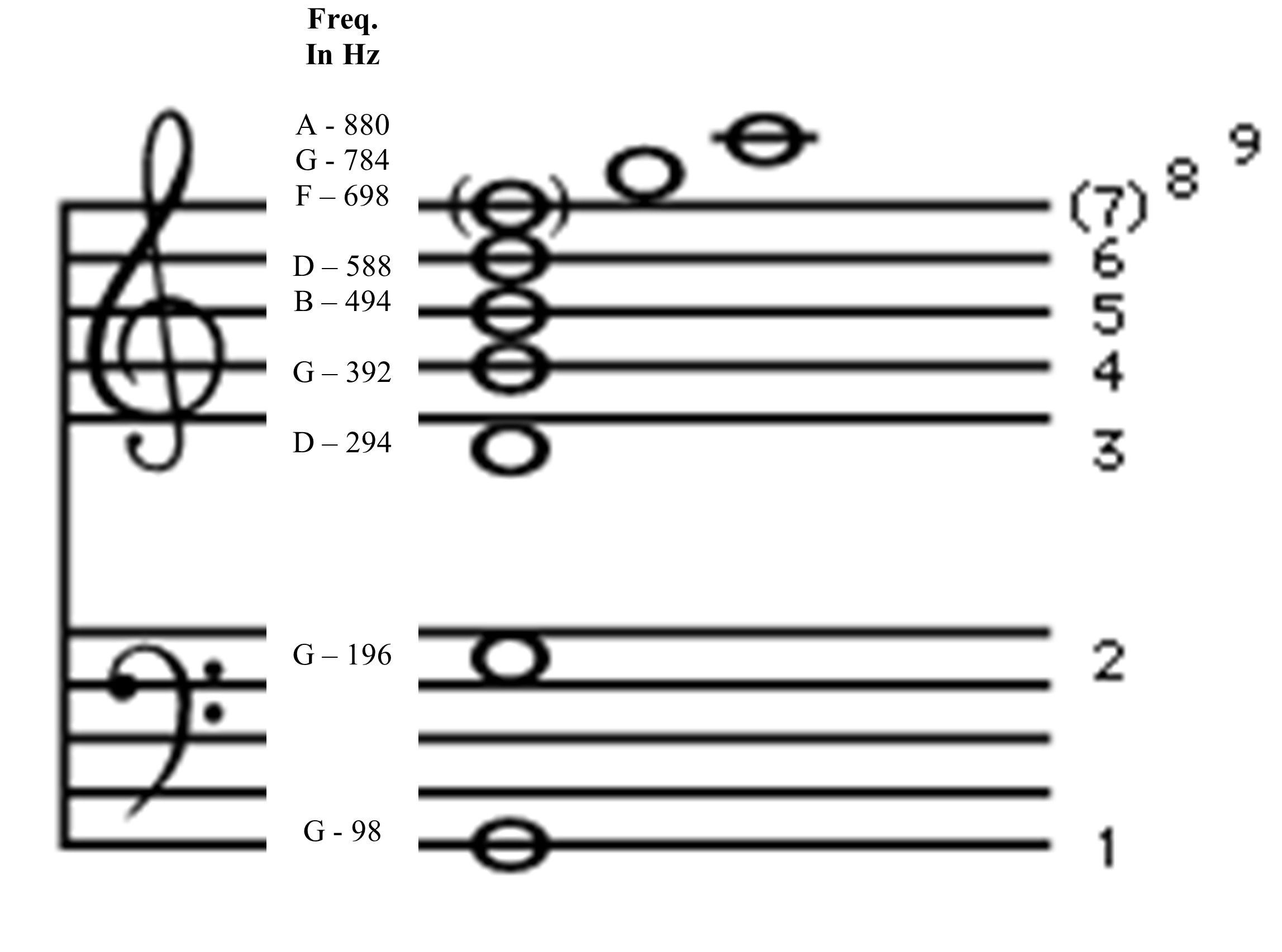

Simply put, when a note (the Fundamental in the series) is played or sung, there are other notes (overtones) that also sound above the original note. The diagram below shows where these extra notes sound in relation to the original. You’ll notice that the first two overtones are relatively far apart. As they stack up on each other the distance becomes smaller and smaller.

Also, keep in mind that sounds seem louder to the human ear between 2,000 and 5,000 Hertz (vibrations per second). For that reason, any overtones in that region tend to sound more dissonant than others. Even though the primary overtones don’t often reach those frequencies, each not in the overtone series has its own overtones, which tend to be closer in that 2kHz to 5kHz region.

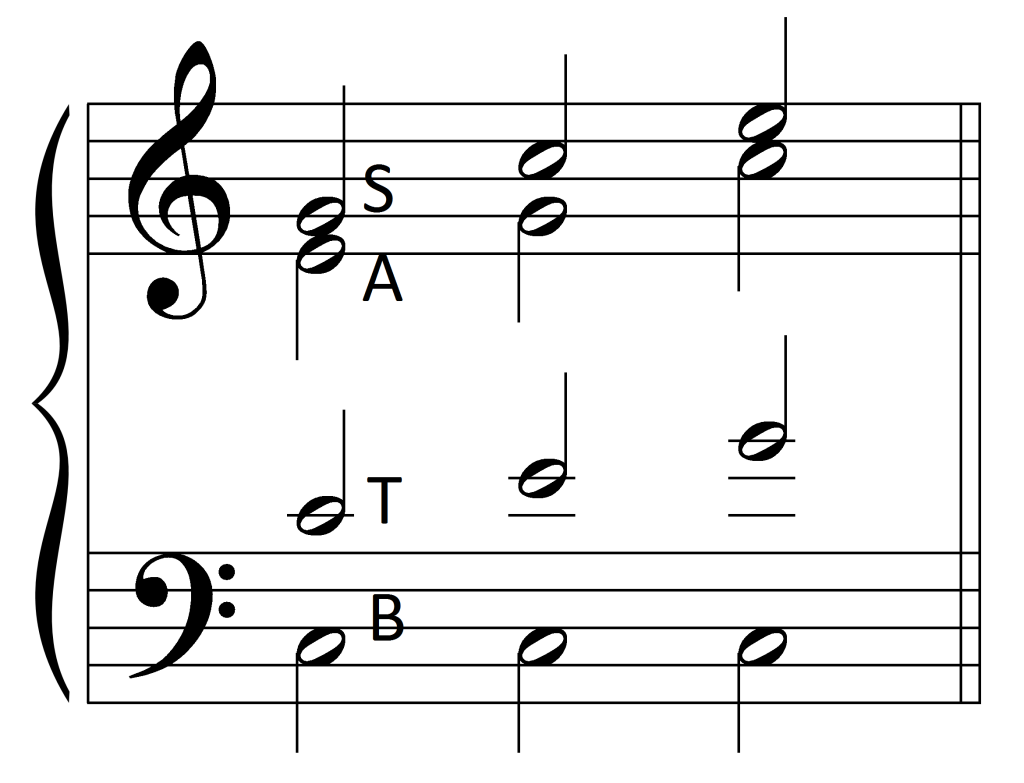

Let’s explore the primary impact that the overtone series has on vocal writing and arranging. Below is a portion of the first verse in which the sopranos and altos sing a duet. Notice that the second chord uses a major second for the harmony.

Now, look below for a bit of verse 4 in which the tenors and basses sing a duet with the melody in the tenor part. You’ll notice that the harmony in the diverging parts do not include a minor second as in the female parts. It is, instead, a minor third, which is farther down on the “stack” of overtones and creates very little, if any, dissonance in the listeners’ ears.

This use of the Overtone Series by composers and arrangers is often achieved through gaining music theory knowledge and years of experience. Perhaps this simple explanation will help explain why the theory and practice work well to create or avoid certain intervals, chords and phrases.